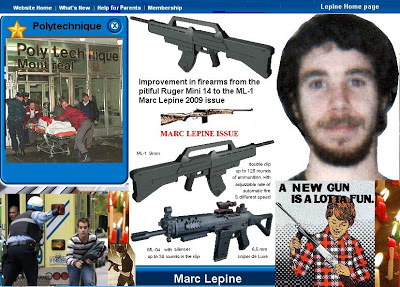

The essay below was written in the winter of 1989. That previous summer, I returned to Vancouver after having lived in Toronto the previous two years. It was a year and time of great transition. The date on the original essay is December 28, 1989, and about 3 weeks after the Montreal Massacre. That was the moniker later given to the shooting spree by Marc Lepine who killed 14 female students and wounded 10 more at the École Polytechnique in Montreal.

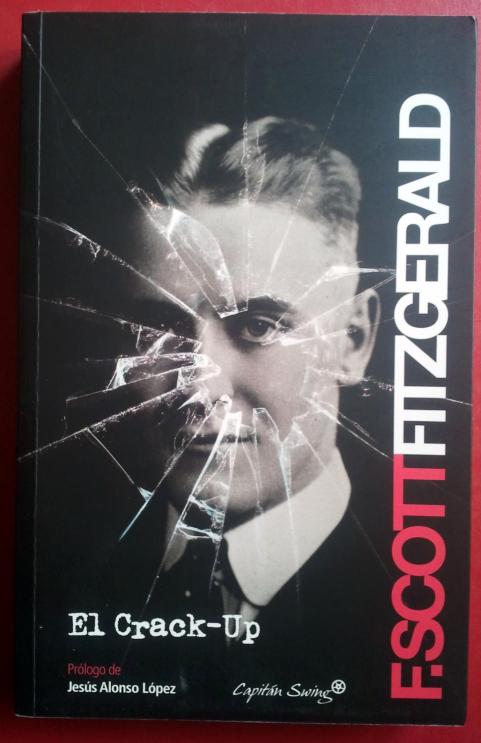

Twenty-four-years later, that incident is still Canada’s most notorious and highest-count killing spree. Hence, the reference to Lepine in my essay’s new title. It was originally entitled “The Comeback.” It was a response to F. Scott Fitzgerald’s “The Crack Up,” a highly confessional essay about his mental break down and general misanthropy, which, unfortunately, had rubbed off on me. A comeback is, of course, the opposite of a crack up, and I meant my essay as a rebuttal to Fitzgerald’s essay.

However, in reading my essay today, I think I was really trying to tackle the big issues of the day, and the most topical and biggest one then was the Montreal Massacre. Ostensibly, I was trying to come to terms with the meaning of life in the context and backdrop of a national tragedy that had had a profound impact on just about every Canadian at the time.

I still remember, all these years later, my mother being seized with so much fear that she irrationally asked me to be her bodyguard to accompany her whenever she had to go out in the week immediately following the massacre — we lived in Vancouver, 4 thousand miles away from where the killings took place. This gives you an idea of the oppressive mood in the country during that godawful winter of 1989.

Surrey, August 15, 2013

Update: December 3, 2015

Yesterday another mass school shooting occurred in San Bernardino, California. According to a CBC news report last night, as of 2010, a mass shooting occurs every 60 days now in the United States. Prior to that, when my essay was written in 1989, mass shootings were rare—1 in every 260 days, according to the CBC [Communist Broadcasting Corporation].

There are some who believe these mass shootings are hoaxes and are staged by the Government, or at the very least have the foreknowledge of the Government. But why is the Government or The Powers That Be (TPTB) staging these horrible hoaxes and or false flags?

An armed American populace is a real threat to TPTB and this is why some believe there is a sinister agenda to take away their guns. If the American public ever found out what was really going on and how royally they have been screwed by the bankers and their puppet politicians, they would all be shot.

Think about it for a minute, do you think politicians really care if we killed one another or them?

The right to bear arms is a right guaranteed by the American Constitution; actually the 2nd Amendment was added on later by the founding fathers precisely because they sensed things might go south, even with a Constitution, and hence they made sure they had the right to bear arms in order to protect themselves from a tyrannical government.

PS

I rarely ever watch television or the CBC any more, not since about 2 years ago when I realized it was a subtle form of brainwashing and programming. They don’t call it TV programming for nothing. The CBC is actually Canadian Broadcasting Corporation; but I find it an insidious propaganda outlet run by Jews and why I call it the Communist Broadcasting Corporation. (Communism was funded by Jew bankers.) Recommended: Nobody Died at Sandy Hook by Jim Fetzer

I was twenty-three-years old and the year was 1983. That was the year that I was involved with an older woman, my English Professor. That was also the year that I read F. Scott Fitzgerald’s “The Crack Up.” My lover was sophisticated, cynical, and sixteen-years older than me. She influenced me, of course. She formed me. And as I think back now, after four years of loathing my fellow man, loathing the stupid and mediocre of the species, I realize that Fitzgerald’s “The Crack Up” also formed me. I now realize that I had had my own crack up. But whereas Fitzgerald didn’t have his crack up until his late-forties, I had mine when I was in my mid-twenties. At least I beat him at something.

It has been demonstrated by writers no less talented than Marcel Proust that autobiographical writing, when it approaches great literature, will benefit all of mankind. Indeed, Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past is vastly superior to Fitzgerald’s “The Crack Up” — the two aren’t even in the same league, as far as I’m concerned. And as I think of Proust, and how he obsessed over the Dreyfus case, I also think of John F. Kennedy, famous public figures who we do not personally know, as Proust did not personally know Captain Alfred Dreyfus, and yet we know them like we know our own fathers and mothers. We (those of us of a certain age) remember where we were when Kennedy was assassinated. We all grieved, as we would have, if a member of our own family had been cruelly and suddenly taken away from us.

Paradoxically, it could be said that Kennedy’s death has a life of its own. By happenstance, the assassination was filmed by an eyewitness named George Lucas Zapruder. By now, 26 years after the event, his film has probably been shown on television hundreds of times and seen by tens of millions of people all over the world. We have all been made eyewitnesses after the fact, if not eternal voyeurs. We are there vis-à-vis his film as the bullets whiz by. We are there when the fatal bullet blasts off part of Kennedy’s skull. The thing is live and alive. Kennedy’s assassination is the American Tragedy that has usurped the Greek Tragedy and the Zapruder film is the never-ending Greek Chorus of our times, albeit a silent one. It plays like a silent movie on a continuous loop in our heads. The assassination occurred almost 30 years ago, and yet it is as fresh in our collective memory as if it occurred yesterday. You only need to see the film once. Once you’ve seen Kennedy’s red brains blasted out in Technicolor, you do not ever need to see it again. It will forever haunt you.

How does the historian, the storyteller of our shared and collective past, compete with the Zapruder film? Truly, one picture is worth a thousand words. As far back as the late ‘twenties, Fitzgerald bemoaned the sorry state of the man of letters. He foresaw the doomed fate of the novelist and writer competing with motion pictures, competing and losing miserably. And although he diagnosed the illness, he could not resist Hollywood, writing screenplays for a paycheck to pay off his debts; hating it, and eventually drinking himself to death. There are no second acts in American life, he famously quipped, and so he should know. He could not repeat his phenomenal success as a novelist of the early 1920s — The Roaring Twenties — and that was how and why he ended up in Hollywood. Fitzgerald is a tough if not impossible act to follow. He wrote when the Hollywood system was at its most efficient, when writers were on contract and movies were manufactured as if on an assembly line in a Detroit automobile factory.

What options are left for intelligent men of today like myself with literary ambitions? Literature arguably died with the coming of motion pictures, or moving pictures, as it was then called. But the motion picture industry of today is virtually impossible to break into now. You need an agent these days just to get your feet in the door, and I wouldn’t even know how to go about finding an agent in the first place. Old Hollywood or the golden age of Hollywood was the 1930’s; Fitzgerald’s arrival in Hollywood was in 1937, when it was at its zenith. He would die on December 21, 1940, a good time to die, I suppose, if he didn’t want to see the fall. But the fall would not occur for another 20 years, not until the 1960s, when the curtains finally came down on the old Hollywood studio system.

For so long I had wanted to be a “SUCCESS,” in capital letters, just like Fitzgerald, but was not. The drive to be a success consumed me, as it had consumed Fitzgerald. Looking back, I think it was rather silly of me to expect so much and at so early an age. My crack up at 28 was rather premature, if not unheard of in literary circles. But at the time, that was how I saw myself, as a great writer yet to be discovered. I say that half-seriously and half-jokingly. In any event, nothing had gone as planned. My career as an academic had been stillborn, and I had long abandoned it as a dead thing. My clique of smart and hip friends at university was no more. It had disbanded after graduation. Friends scattered all across the country looking for work and just naturally getting on with their lives after university. I now regard those years spent at university as the best years of my life. My memories of that period immediately after graduation are bittersweet. But the most painful of all, my relationship with the love of my life — that, too, was over, though to this day, no one really knows why it ended and neither one of us is willing to admit who finally dumped whom?

At the age of twenty-seven my life in Vancouver was quickly going down the toilet, just as Vancouver was also going down the toilet. The city was experiencing its biggest economic depression of the century. On the other side of the country, Toronto was booming and everybody with half-a-brain was already there by the winter of 1986. In the summer of 1987, I finally set out and drove four thousand miles across Canada to Toronto. Actually, I drove to Toronto with my high-school pal, Jimmy, (James Gaylie) who had also recently broken up with his girlfriend and was at a low point in his life and needed to get the hell out of Vancouver, too. There were good times in Toronto, naturally. We were all still relatively young and still on the prowl, though I don’t remember having much enthusiasm for it or any luck, to be honest. In terms of emotional sustenance and romantic relationships, those two years in Toronto were barren like a desert. I was unable to love anyone else, really. For a brief period of about three months, I was involved with another woman, but that relationship was doomed to fail from the start, or at least I took every opportunity to sabotage it. Consequently, there were times, perhaps sitting in a café by myself, or lying in bed alone, I would weep inexplicably and uncontrollably. How pathetic!

Why had I chosen this lonely and loveless existence? Why didn’t I take the safe route? Why did I instead gamble away my professional career and chance for marital happiness on this reckless and selfish life of the bohemian artist? Was I deluded in the belief that I could beat the astronomical odds of achieving the immortality of the great artist? And in Canada!? — not exactly a country with any sort of distinguished cultural history or history, for that matter. Why was I such a miserable underachiever, was what one of my new friends in Toronto (film-maker, Les Rose) ironically asked me, without knowing that he was being ironic or idiotic, of course.

Why, indeed, was I such a loser? I remember ever since I was a young 9-year-old boy, the story of Vincent van Gogh moved me deeply and irreversibly. And later in my teens, as I was drawn to music, I was also drawn to Bix Beiderbecke, the tragic jazz cornetist who died at the age of twenty-eight. He had been my teen-idol, a queer choice for a teen-idol, I know, but I had always been unconventional, even during those hormone-charged teen-years of conformity. Upon reflection, I think I was more enamoured with his myth than with his music. Beiderbecke was a contemporary of Louis Armstrong. But he pales by comparison to Armstrong who revolutionized jazz and had a long and great performing and recording career that did not end until his death in 1971 at the age of 70. But then again, I have always had a perverse fondness for the hopeless underdog, for those who died young and left a beautiful corpse. I took it at face value if not as my destiny that I would somehow replicate Beiderbecke’s life and die before I turned 29. But after having reached my 29th birthday and coming to the realization that an early, tragic death is not in the cards for me, I am faced with the sobering task of figuring out just what the heck it is that I want to do for the next 40 to 50 or more years that I still have left on this earth.

Two weeks ago, a twenty-five-year-old man by the name of Marc Lepine went on a rampage at the École Polytechnique at the University of Montreal. He specifically targeted female engineering students and murdered 14 of them in cold blood. He also shot and wounded 10 more students who survived the massacre. Then he shot and killed himself. Lepine carried on his person a three-page diatribe against prominent and successful women in Quebec society and feminists in general. In his diatribe, he also claimed as his hero, Denise Lortie, another lunatic whose claim to fame was killing 3 people during a shooting spree inside the Quebec legislature in 1984. Was Lepine a copycat killer? Investigators later revealed that Lepine was a ‘war film freak,’ as if that explained anything. Or does it?

The American counterpart of Marc Lepine is Patrick Purdy, the twenty-four-year-old man who gunned-down school children at play in Stockton, California on January 17, 1989. He killed 5 children and wounded 29 others before shooting himself in the head. Purdy, we are told, was a ‘horror film freak.’ He was a Freddy Krueger fan, and his favourite movie was “Freddy Stalks Manhattan.” One wonders why instead of inscribing the name of Freddy Krueger on his AK-47 assault riffle, Purdy chose to inscribe the acronyms and symbols of Hezbollah, the Islamic militant group in Lebanon. What was Purdy’s connection to that group and why was Hezbollah killing Asian kids in Stockton? Curiously, this was never really explained. But true to form and profile, both Lepine and Purdy were quiet loners. This is perhaps less comforting than if they had been raving and ranting lunatics during their killing sprees. One witness who survived the Stockton shooting recalls that, ‘He was not talking. He was not yelling. He was very straightforward about it. He was not frowning. He just did it matter-of-factly.’

![Patrick Purdy [Misc.]](https://joecanuckblog.files.wordpress.com/2015/12/131212_crime_stocktonshootingcrimescene-crop-original-original.jpg?w=700)

However, it needn’t be described so scientifically or so rhetorically rather, since by doing so, Caputo convincingly explains away a crime that he had earlier claimed could not be explained. Instead of the Racist Narrative or the Manchurian Candidate Narrative, or the Psychiatric Narrative or the Drug-crazed Killer Narrative, all of which Caputo dismisses, he unintentionally confers upon us the Theoretical Physics Narrative. In this respect, Caputo gives coherence to a crime that he claims has no coherence. Here, for example, is a passage by Caputo that seems to me to be unwittingly giving cosmic and literary significance to a heinous crime that does not deserve any:

“It was the absence of a motive that gave the massacre the awesome power of the inexplicable. It awakened within us the dread of the unknown that neoliths must have felt when the tops blew off mountains, or lightning bolted from the primeval skies to blast their kinsmen out of existence. Early man helped manage his awe of such disasters by ascribing them to angry gods or evil spirits, but we like to think of ourselves as far beyond such barbaric hocus-pocus. Why, we’re even beyond the historically more recent hocus-pocus of clergymen, who might have said of Purdy what Joseph Conrad said of Mister Kurtz: his mind was sane but his soul was mad; that is, he had been seized by the power of the Devil. None of that for us in post-industrial, post-Freudian, post-modern microchip America; we are a technological people beyond gods and devils. We want our dread explicated. By uncovering a motive for Purdy’s crime, we hope to create a classical, coherent narrative with a beginning, a middle, and an end, cause and effect.”

But Purdy’s crime, or for that matter, Lepine’s crime is not without a motive. In Lepine’s case, he hated women and simply wanted to kill them. In Purdy’s case, he hated Asian immigrants because he believed they took jobs away from Americans. He couldn’t find a job or when he did, he couldn’t keep it, and so he blamed the “gooks.” The kids he killed at the Cleveland Elementary School were Cambodian and Vietnamese immigrants — children of refugees who escaped the bloodbath of the Vietnam War only to be executed in a schoolyard in Freedom’s Land. The irony and pathos were just too much and too heart-wrenching. How many millions were killed in that preposterous war against communism? Why is it socially acceptable to kill innocents overseas but not on one’s own native land? Had Purdy and Lepine actually joined the armed forces instead of pretending to be real soldiers would their indiscriminate slaughter of innocents in distant lands even be reported in the media? Both men were literally dressed to kill: Marc Lepine in his hunting regalia and Purdy in his Rambo getup.

No one mourned or will ever mourn for them. They were monsters. But why were they monsters? Were they born monsters; and if not, who or what made them monsters? Why is it so often the case that a young man will kill a dozen or so strangers for no other reason than he is pissed off at somebody or at some group of people, but the actual culprits who are to blame for the young man’s problems, real or imaginary, are never the ones who get their comeuppance? It’s always innocent bystanders who get killed. Alas, precision was not a virtue valued by either Lepine or Purdy. Precision is not likely to be looked upon as a virtue by people who are essentially illiterates. A culture and civilization that does not read or does not want to read is doomed. This generation that has been weaned and brought up on television and mass media has already produced an inordinately high number of violent killers and criminals in our bulging prisons and will continue to produce more psychopaths in the future, unless we do something to stop this.

No one mourned or will ever mourn for them. They were monsters. But why were they monsters? Were they born monsters; and if not, who or what made them monsters? Why is it so often the case that a young man will kill a dozen or so strangers for no other reason than he is pissed off at somebody or at some group of people, but the actual culprits who are to blame for the young man’s problems, real or imaginary, are never the ones who get their comeuppance? It’s always innocent bystanders who get killed. Alas, precision was not a virtue valued by either Lepine or Purdy. Precision is not likely to be looked upon as a virtue by people who are essentially illiterates. A culture and civilization that does not read or does not want to read is doomed. This generation that has been weaned and brought up on television and mass media has already produced an inordinately high number of violent killers and criminals in our bulging prisons and will continue to produce more psychopaths in the future, unless we do something to stop this.

But what exactly must we do to stop these massacres? How about asking the right questions and addressing the real issues that afflict our society? How about “the disinterested pursuit of truth,” as Mathew Arnold proposed? However, when the world is going to hell in a hand-basket, as ours is, the disinterested pursuit of the truth may be too abstract and too difficult for many. The good news is that there is a literacy campaign sweeping across North America at the present moment. Will the good-intentioned people behind this campaign be able to make a difference with the hoi polloi? When people become more literate, does it follow that they will also become more civilized and stop killing one another? Would it have made any difference had Marc Lepine or Patrick Purdy spent more time reading the classics instead of wasting their time and minds on dumb-ass junk movies? My mind boggles at this fantastic thought.

I began this essay with F. Scott Fitzgerald and his confessional essay, “The Crack Up.” It was the model that I had in mind for this essay, which is my confession of sorts, my way of exorcising my demons. However, it has come as an ironic revelation to me that the greatest demon that needed to be exorcised away from my life was none other than Fitzgerald himself. I think I read him too early in my life. In retrospect, I think I read too much literature too early in life. It has led to a very lonely existence in this world populated by not a whole lot of people who share my interests and worldview. Fitzgerald wrote “The Crack Up” towards the end of his bitter life. I never should have read it as young as I did. It is not an essay for young men to read, especially impressionable ones with delusions of artistic grandeur and fame. I read it when I was 23 and it nearly killed me with self-pity and bitterness. Luckily, my crack up occurred when I was 28 and I am slowly but surely recovering, if not fully recovered. At 29, I still have a lifetime ahead of me. It’s time to finally say goodbye to Fitzgerald and move on, as they say.

Vancouver, December 28, 1989