Preface:

This essay was written in 1983 (when I was 23) for a 17th-century English literature course that I took at the University of British Columbia (UBC) — a mandatory course for my Bachelor of Arts degree in English Literature, which I obtained in 1985. I started typing this 3,033-word essay about a year ago and only finished today because I find this essay too academic or too literary, really, too esoteric for the general public, and that was the reason why I procrastinated for a year in publishing it online, knowing that hardly anyone except the Zionist agents and paid trolls who read everything I write these days would bother reading it. At least I know I do have a dedicated, albeit small Jewish audience for my essays on literature.

My professor was Dr. Harriet Kirkley. She would be in her late-70s or early-80s if she is still alive and may remember me. How could she forget? I told her or rather I wrote “Fuck off” on my final examination, which I self-destructively wrote for her before storming out of the classroom; that, I still remember vividly and so should she if she’s not senile. I don’t remember why I was so angry but this first essay I wrote for her in which I expressed my contempt for Orthodoxy and The Establishment probably had something to do with it. (I was your typical brainwashed Marxist Useful Idiot and Bully who now populates the ultra Jewish politically-correct universities today, but in the early 80s I was the exception not the convention. Rereading my essay, I now see that I had mistakenly projected my Marxist/Jewish rebelliousness unto John Donne.)

It’s truly amazing in hindsight that she didn’t give me a “F” for “Fail” but gave me a “P” for “Pass” for the course, which considerably dragged down my grade point average, though I don’t really think I cared at that stage in my not-to-be “academic career”. Guess what? I’m still bucking the system at 55-years-of-age; this time I’m in the biggest fight and perhaps the most meaningful fight of my life against the Jew World Order. (If you are new to this site and to my writings, skip over the next sentence if you don’t wish to be shocked.) I became Jew-aware about 2 summers ago and I am the founder of “Justice For Chinese” which, at the moment, is a loosely organized group of individuals attempting to seek an apology and compensation from the Rothschild and Sassoon Jews who destroyed China with opium 200 years ago and whose descendants, believe it or not, are still in control of the worldwide drug trafficking today via their Intelligence Agencies such as the CIA, MI6 and MOSSAD.

My memory is fuzzy after over 32 years but I think we forgave each other in the end; and if I remember correctly, she even purchased a copy of my self-published poems, which I shamelessly peddled door-to-door at the UBC English Department after my graduation circa late-1985 or early-1986. In any event, for this particular essay, she gave me an “A” mark and this is what she wrote on my essay: “An intelligently perceptive discussion that makes some sense of that poem, well written on the whole and stimulating. You might enjoy Donne’s “Love’s Progress” and some of the more sexually explicit elegiacs which, in some sense, support your analysis of public/private, spontaneous/collective dichotomies, but which also gave the lie to modern notions of “repression” as a major force in the 19th century sensibility. It may well have been there, but they didn’t worry so much about it as a rule.”

Clearly, Dr. Kirkley did not think that sexual repression played any part in Donne’s poetry and was quite annoyed by my suggestion halfway in my essay that it did. She responded by writing, “Donne’s society was not Victorian and sexual repression is more modern than the 17th century when it didn’t exist in the same way.” I agree. I had been greatly influenced, or rather brainwashed by reading the demented Jew, Sigmund Freud, in Dr. Fred Stockholder’s course on Literary Criticism, which probably and properly screwed me up good, as they say, no pun intended.

Surrey, British Columbia, September 25, 2015.

There is so much to say about John Donne, yet I have so little space in which to say it all. That is, I am not unaware of the rules involved in writing an undergraduate paper: that you begin with a beginning, a middle, and then, the end, which is a recap of what was said in the beginning and the middle: all really structured if not contrived and redundant by the end. Hopefully, and if it is not outside the powers of your intellect, you do so logically, analytically, and coherently like: A + B = C because A = 1, B = 2, C = 3; therefore A < B, B < C, and C > B or A.

But if “one plus two make three” is logical, it is also ARTIFICIAL, as is its essay equivalent because both become invalid when men, who created them in the first place, no longer deem such constructs valid. In other words, “one plus two make three” exists not in nature, but in man. It is a man-made phenomenon. “One plus two make three” does not represent the natural order of things any more than the “coherent, logical, and analytical” essay represents the natural processes of the mind, which, almost without exception, is anything but coherent, logical, and analytical.

Is it not obvious that all the rules have, as a rule, the inherited biases of men who invented them and or who choose to live by them? You must use the big spoon for the soup! Why? Because those are the correct rules, that’s why! But what if I don’t want to use the big spoon or no spoon at all? What if I don’t want to play by your rules? Does that make me a “pig” in your eyes or a “dangerous dissident”? Why do you insist that I play by your rules, to be a slave to your orthodoxy? In short, what if I want to buck the system and to destroy the established hierarchy?

Of course, rebellion and the destruction of the hierarchy cannot occur without the consciousness of being oppressed: it is only when you are able to see the chains that you may begin to smash them to pieces. With respect to the literary essay, the objective is to break the convention or break away from the convention. But insofar as one cannot really ever totally break away from society and its conventions, no one can truly and totally be original. Rather, the best we can do is to arrive at a synthesis. This synthesis, this compromise, however, is not without tremendous tension, is not without colossal conflict in John Donne’s “The Extasie”.

Though the giant step from “I” to John Donne is, of course, an abrupt transition, perhaps too abrupt; nevertheless it illustrates and parallels the jarring synthesis of ideas seeming to be unrelated that one is confronted with in the opening lines of Donne’s “The Extasie”: “Where, like a pillow on a bed,/A Pregnant banke swel’d up, to rest/The violets reclining head.” Indeed, similes are a kind of synthesis; they bring together two opposites, and in Donne’s opening lines, much more than two. For example, the comparison between a “pillow” with a “banke” that is like a woman who is “Pregnant” hence “Pregnant banke,” which further implies that Nature is feminine and in the process of regeneration, is evidence of a compact condensation, of a tight synthesis of diverse elements combined together not so much out of kinship as out of opposites i.e., positive end of one magnet attaching itself to the negative end of another magnet.

But if the synthesis of diverse elements is not merely superficial and simplistic, as in “My love is like a red rose”, surely it is a deep and complex one, involving a synthesis of not only diverse elements per se, but of the socially unacceptable thoughts evoked precisely by such a synthesis of diverse elements, for the implicit sexual overtones of “bed” followed by “pregnant banke” certainly undermine the Platonic matter-of-factness of “Sat we two, one another’s best”. Essentially Donne’s opening lines are private expressions which are not unlike the private symbols of one’s own dreams, and they, these private symbols, are, I would argue, and perhaps in too Freudian a way, the consequence of repression. How does one celebrate sexuality in a society that suppresses sexuality? For Donne, highly compact language is one way, just as the private symbolism of our dreams is another.

As sexual repression induces frigidity, or in Donne’s case, rigidity (“Wee like sepulchrall statues lay”) procreation finds an outlet in another form: “So to ‘entergraft our hands, as yet/Was all the means to make us one,/And pictures in our eyes to get/Was all our propagation”. And although the two lovers are in a spiritual sense “one”, this oneness, this synthesis is unsatisfactory, is full of tension and harshness, as if what is happening is not love, but war: “As ‘twixt two equall Armies, Fate/Suspends uncertaine victorie”. Was this the 17th-century version of our Post-Freudian modern day Battle of the Sexes?

In the next lines, the battle, if I may continue to use that word or metaphor, to transcend the body is won, or so it seems, when a higher state of being is metaphysically achieved in: “Our soules, (which to advance their state,/Were gone out,) hung ‘twixt her and/mee”. Hence, the movement is towards the gravity-free elevation where, “suspend[ed]”, the “soules negotiate”, away from the body, away, really, from the world and all its rules, regulations, disease, destruction, and death. I would argue that Donne’s desire to transcend the body is the same as the desire to transcend time — or what I would call “collective time.”

As a matter of fact, and whether Donne was conscious of this or not, the shift from the personal point of view (We) to the more distant or third person point of view (He): (“he though he/Knowes not which soul spake/Because both meant, both spake the same/Might thence a new concoction take”) underlies the soul’s departure from the body, underlies the soul’s departure from the world. Thus, a new “time frame” for the bodies knows no decay or death: “Are soules, whom no change can invade”: Time Suspended! Or to use a modern term, Suspended Animation: “We see, we saw not what did move/But as all severall soules containe”. Here, the idea of time dilation is conveyed in the ambiguity of tense, “wee see” immediately followed by “we saw”. That the tense is inconsistent, not either present or past, but both present and past implies a synthesis of time or timelessness: past and present are one! This is what I mean by Einsteinian Time. Please see end notes for a detailed explanation of time dilation and Einsteinian Time.

And although it is true that Donne is quite firm in qualifying the synthesis of the souls, “Wee see by this, it was not sexe”, what takes place in the succeeding lines clearly contradicts this qualification: “Love, these mixt soules, doth mixe againe,/And makes both one, each this and that/A single violet transplant,/The strength, the colour, and the size,/(All which before was poore, and scant,) Redoubles still, and multiples.”

In the above lines there is the intimation that the problem may exist not so much with the individual but with the environment in which the individual lives: for what is infertile is not the violet, but the soil; because once transplanted, the once poor violet redoubles and multiples. Perhaps Donne is alluding to societal conventions and constraints that do not permit the lovers to consummate their love, which may, after all, be a sordid love affair between people from different classes in a very class-conscious 17th-century England. Perhaps the lady was ‘playing hard to get’ and the sexual tension was par for the course, if not part and parcel of the eternal mating game and natural order of things. Nevertheless, by the end of the poem, and reading between the lines, as the saying goes, we know that the two lovers did consummate their love.

Whereas earlier in “The Extasie” the conflict between Physical love and Spiritual love was solved by the soul’s departure from the body, though not really or not literally, the synthesis of the body and soul in the last line of the poem, “Small change, when we’re to bodies gone” presents no real problem insofar as the conflict between the sexual desires of the poet i.e., Eros, and the ideal and abstract love demanded of the larger community i.e., Agape are now interchangeable. Consequently, through the interchangeability of the union of the souls and the union of the bodies, physical love has been elevated, while at the same time, the abstraction of this physical love has been, well, brought back down to earth, as the pragmatists are wont to say.

However, in order for us to believe that the “animation” of the “mixt soules” is now interchangeable with the lifelessness of the “sepulchurall statues”, we must force ourselves to believe that talk is better than action, when we know very well that talking about sex is no substitute for the sex act itself, nor as pleasurable, for that matter. Moreover, one strongly feels that the person being addressed by the poem is not the poet’s lover, but the poet’s audience. At best, if “The Extasie” is not foreplay, it is a dramatic monologue addressed to the outer world at large; and as such, the poet is highly conscious of both the rules involved in the love game and also the rules involved in poetic expression.

For example, the first ten lines of “The Extasie” is an interlocking rhyme scheme of ABABAACACB, affecting the effect somewhat like the image of “Our eye-beames twisted, and did thread our eyes upon one double string”. And although no consistent rhyme scheme occurs between lines 10 to 40, affecting, appropriately, the randomness and spontaneity of the dramatic monologue, the rhyme scheme of the synthesis of the souls in lines 41-48 is uniformly based on the vowel “O”, emphasizing the unity or singularity of the souls: “When love, with one another so/Interanimates two soules,/That abler soule, which thence doth flow,/Defects of lonelinesse controules,/Wee then, who are this new soule, know”.

Notice too, that the internal rhyme of these lines is also based on the soft “O”, affecting both the unity and coalescence of the souls. From line 50 onward, the rhyme scheme is again an interlocking one, one which picks up consistency as the poet gains linguistic if not sexual confidence by the very end of the poem, when Donne demonstrates with sound — prudes, brace yourselves — the forbidden images of intercourse: “And if some lover, such as wee,/Have heard this dialogue of one,/Let him marke us, he shall see/Small change, when we’are to bodies gones”.

With the exception of “gone”, which is an eye-rhyme of “one”, all the rest of the end rhymes of the last fifteen lines intertwine, one with another, so that the development of the ending proceeds in a set sequence; so that the displaced image of insemination and womb development, if I may make a creative and penetrating assertion — puns intended — appear in the structure of the poem itself!

But whereas in “The Extasie” the tension caused by the desire of the poet for sexual love (Eros) and the desire of his community for spiritual love (Agape) gave us the ideal synthesis of body and soul, if only conceptually, the synthesis of similar tensions in the “The Anniversarie” is less convincing and more paradoxical. For although the poet begins by defying collective time in “The Anniversarie”: “Only our love hath no decay;/This, no tomorrow hath, nor yesterday”, he will, by the end of the poem, succumb to it: “Let us love nobly, and live, and adde againe/Years and yeares unto yeares, till we attaine/To write three-score, this is the second of our raigne”. Unlike in “The Extasie”, Donne seems to understand that the synthesis of body and soul and their spiritual ascension may be nothing more than a dramatic monologue (directed at his audience rather than to his lady, as I earlier suggested) and that finally all things in this material world decay and die, and so for the short time that we are on this earth, let us love each other passionately and “nobly”, to use his word. Hence, he implores, “Let us love nobly, and live”! Carpe Diem!

Furthermore, what is also paradoxical in “The Anniversarie” is the fact that it is precisely the lovers’ consciousness of each other which brings the heightened consciousness not of subjective time, but of collective time: “The Sun it selfe, which makes times, as they passe,/Is elder by a yeare, now, then it was/When thou and I first one another saw”. Or in “The Good-Morrow”: “I wonder by my troth, what thou, and I/Did, till we lov’d, were we not wean’d till then?” To wit, in the following lines of “The Good Morrow” Donne gives an explicit explanation: “For love, all love of other sights controules,/And makes one little roome, an every where./let sea-discoverers to new worlds have gone/Let Maps to other, worlds on worlds have showne,/Let us possess one world, each hath one, and is one”. Or to put it simply, the lovers complete each other. Separated and apart, they might as well be dead.

For this paper, suffice it to say that Donne’s exploration of subjective reality in “The Good-Morrow”, like his exploration of subjective time in “The Extasie”, begins with and returns to the consciousness of the real world of matter and time. To put it plainly, Donne’s metaphysics is brought back down to earth and grounded by Donne’s commonsense understanding of critical conceptions of time, space, and matter. In “The Good-Morrow” for example, his reference to the hemispheres North and West (“Where can we finde two better hemispheres/without sharpe North, without declining West?”) brings the palpability of reality into the unreality of his metaphysics (“My face in thine eye, thine in mine appears,/And true plaine hearts doe in the faces rest”). In these lines “West” and “North” do not differentiate two spatial points, though essentially that is their function; but rather, Donne employs them to evoke an emotion of living immutability.

Donne’s uncanny ability to translate abstract ideas into concrete images or vice versa; to translate scholastic doctrines into abstract emotions, as, “What ever dyes was not mixt equally;/If our two loves be one, or thou and I/Love so alike, that none doe slacken, none can die”, where he has borrowed, and I am now quoting from the footnotes of the poem, “the Scholastic doctrine that change and death result from inequality or disharmony of the elements of a thing”, demonstrates remarkably Donne’s originality and the constructs of his society in fusion. By constructs, I mean the poem was written in iambic pentameter, the poetic convention of Donne’s times, of course.

Although reality is our own making, as Donne suggests in “The Good-Morrow”, oftentimes we make it correspond with everyone else’s, or at least we try to, especially if the collective’s Agape is in conflict with the individual’s Eros, as was the case in “The Extasie”, in which instance the conflict over the poet for personal sexual love and his community for public spiritual love provided the tension and dichotomy which Donne inevitably synthesized in all his poems, with their strained conceits and rhythmic irregularities. This was distinctly Donne’s genius and is the explanation for his highly personal and private, yet highly formal and structured poetry. He was an English Eccentric and Original!

END NOTES

Time Dilation or Einsteinian Time in John Donne’s “The Extasie”

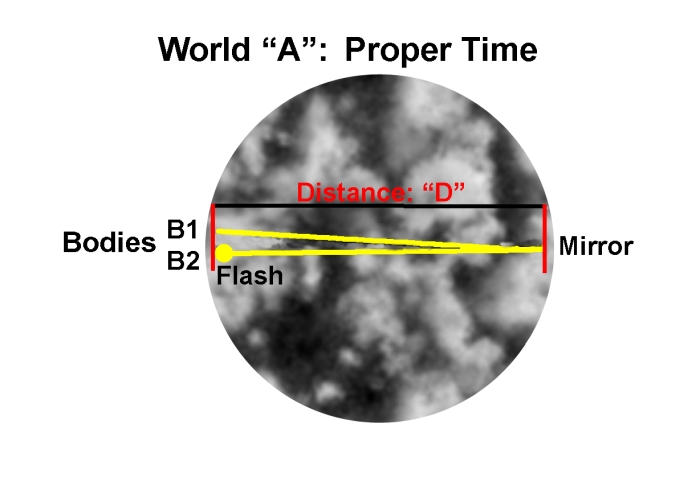

We first consider two bodies (B1 and B2) at rest in “World A”. Both bodies are at a distance from a large mirror (Distance = “D”). Acting as one, both bodies fire a flashgun and measure the interval between the original flash and the return flash from the mirror. See diagram below:

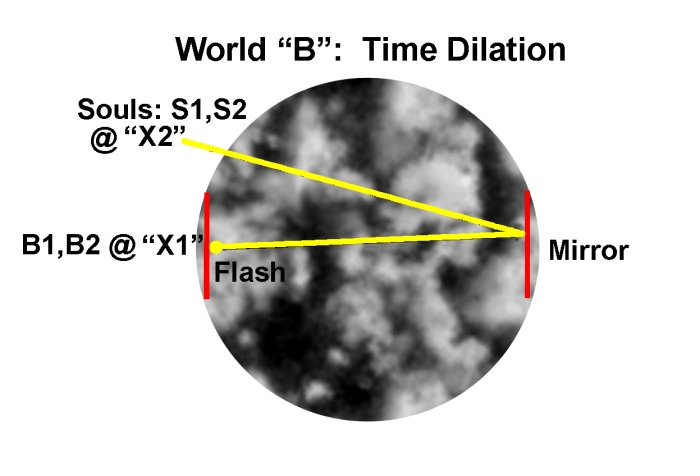

We now consider these same two events, the original flash of light and the returning flash, as observed in “World B”, where the souls are departing away from the bodies. See the following diagram:

If it is true, as Donne believes, the souls are interchangeable with the bodies, the experiment applies to the souls as well as to the bodies. Therefore the events happen at two different places: at X1 and at X2 in “World B” because the bodies “B1” and “B2” have moved a vertical distance. Their souls have left their bodies in other words. Hence, in “World B” we see that the path travelled by the reflection of the flash is longer than in “World A”.

However, Einstein postulates that light travels with the same speed “c” in both World A and World B. Since light travels farther in World B at the same speed, it takes longer in World B to reach the mirror and return. The time interval in World B is thus longer than it is in World A. Observers in World B would say that the clock held by souls (S1 and S2) runs slow since they claim a longer time interval for these events.

Bodies B1 and B2 measure the time of the light flash and return at the same point in World A, while in World B these events happen at two different places. A single clock can be used in World A to measure the time interval, but in World B, two synchronized clocks are needed, one at X1 and one at X2. The time between events that happen at the same place in a reference frame is called “proper time.” The time interval measured in any other reference frame, such as in World B, is always longer than the proper time. This expansion is called “time dilation.”

Though this is, of course, an oversimplification of Einstein’s time dilation, nevertheless, it is, for this paper, sufficient. For more information about “proper time” and “time dilation”, see Paul A. Tipler’s Physics (Worth Publishers, Inc., 444 Park Avenue South, New York, N.Y. 10016) p. 670-671.